New paper for Cristina Alcon

Scientists at the Quadram Institute (formerly Institute of Food Research) have uncovered a new mechanism linking bacteria in the gut to Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD).

Dr Lindsay Hall and colleagues have found that certain bacteria release molecules that interact with the lining of the gut to influence a process known as epithelial cell shedding. This shedding process is vital to maintaining a healthy gut lining, as it ensures that dead cells are replaced with a healthy turnover of new cells. However, in patients with IBD this shedding process happens more rapidly than cells can be replaced. This pathological cell shedding can in turn lead to a ‘leaky’ gut barrier.

IBD has been linked to changes in the community of resident gut microbes, or the ‘microbiota’, before. IBD patients typically have a less diverse microbiota, and are depleted in certain bacterial species. But until now, we have had only limited insights as to why this is important in the context of disease.

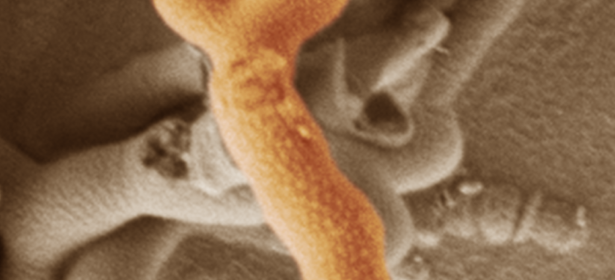

Dr Lindsay Hall, from the Quadram Institute, has been studying Bifidobacterium, one of the major groups of bacteria that make up the microbiota in healthy individuals, particularly infants. Notably this population of bacteria is depleted in IBD patients. In collaboration with Professor Alastair Watson from the Norwich Medical School at the University East Anglia, Dr Hall and her team studied the interactions between a specific human-derived strain of Bifidobacterium (Bifidobacterium breve) in an experimental model that can be induced to increase cell shedding, and mimic IBD disease symptoms. Cristina Alcon, a 2nd year DTP student helped with the immunochemistry analysis, the ELISA tests, and the quantification of caspase 3 analysis.

The study, published in the journal Open Biology, showed that this Bifidobacterium significantly reduced the excessive, IBD-like cell shedding from the gut lining of mice. The researchers identified a specific surface molecule produced by this Bifidobacterium strain that interacts with a protein in the mouse gut lining, which controls the inflammatory, damaging networks that lead to cell shedding. This protein, called MyD88, also exists in humans where it is thought to have a similar role.

“This is exciting evidence of a mechanism that could explain the associations seen between Bifidobacterium, the microbiota and IBD. These findings still need to be confirmed in humans, but if clinical trials are successful, this could point the way to new therapies for IBD and other gut diseases.” Said Dr Lindsay Hall

The research was funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.

Having identified the bacterial molecule responsible for interacting with the host’s cell shedding mechanism, as an exopolysaccharide capsule, the researchers can now carry out genetic screens to find other bacteria that produce it. And a similar approach could be used for other diseases where a role for the microbiota has been implicated, once a mechanistic link has been established.

“With new information relating to these sorts of mechanisms, we may even be able to look at personalised microbiota therapies or ‘probiotics’, where genetic screens are used to match the perfect beneficial bacteria to different individuals” commented Dr Hall.

Image: Bifidobacterium breve. By K.R.Hughes